Tadeusz served with his father in the Home Army. He started his service with the partisans of the legendary Major Dobrzański ‘Hubal’. After the war he fled to the United States where he was drafted into the army, despite the fact that he was not an American citizen. He refused to serve which led to a high profile trial.

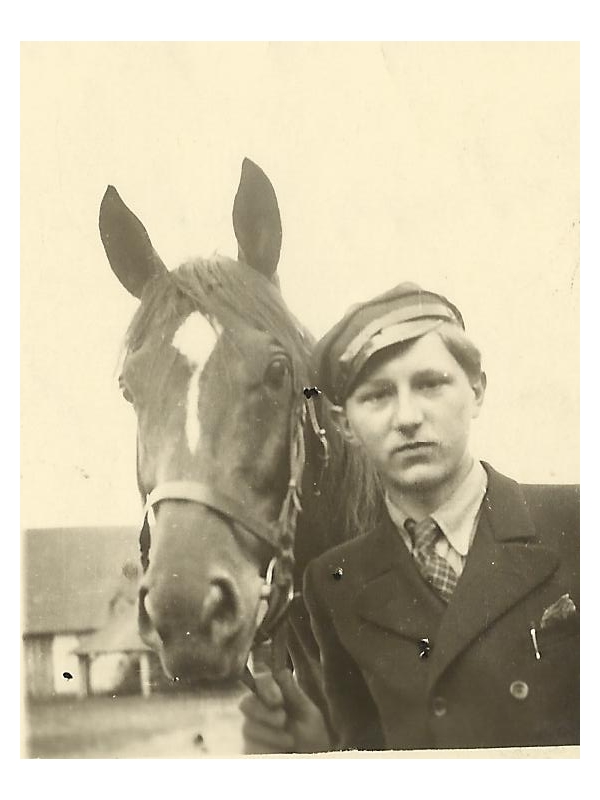

On 1 September 1939, Tadeusz was to continue his education in high school, but the outbreak of the war interrupted his plans. Two months into the war Major Dobrzański ‘Hubal’ appeared in the area where Tadeusz lived. On 28 October, Tadeusz’s father, Jozef, took him to meet Major ‘Hubal’. Tadeusz also met Captain Kalenkiewicz that day. He was the one of the minds behind the Cichociemni (the silent unseen), a elite unit within the Polish resistance. On that day, Captain Kalenkiewicz said to the young Tadeusz: “A nice boy, but he bites [his] nails”. To erase the bad impression, ‘Hubal’ said to Tadeusz: “You will be my youngest soldier, and because today you are having your name day, we will call our first military post Tadeusz”.

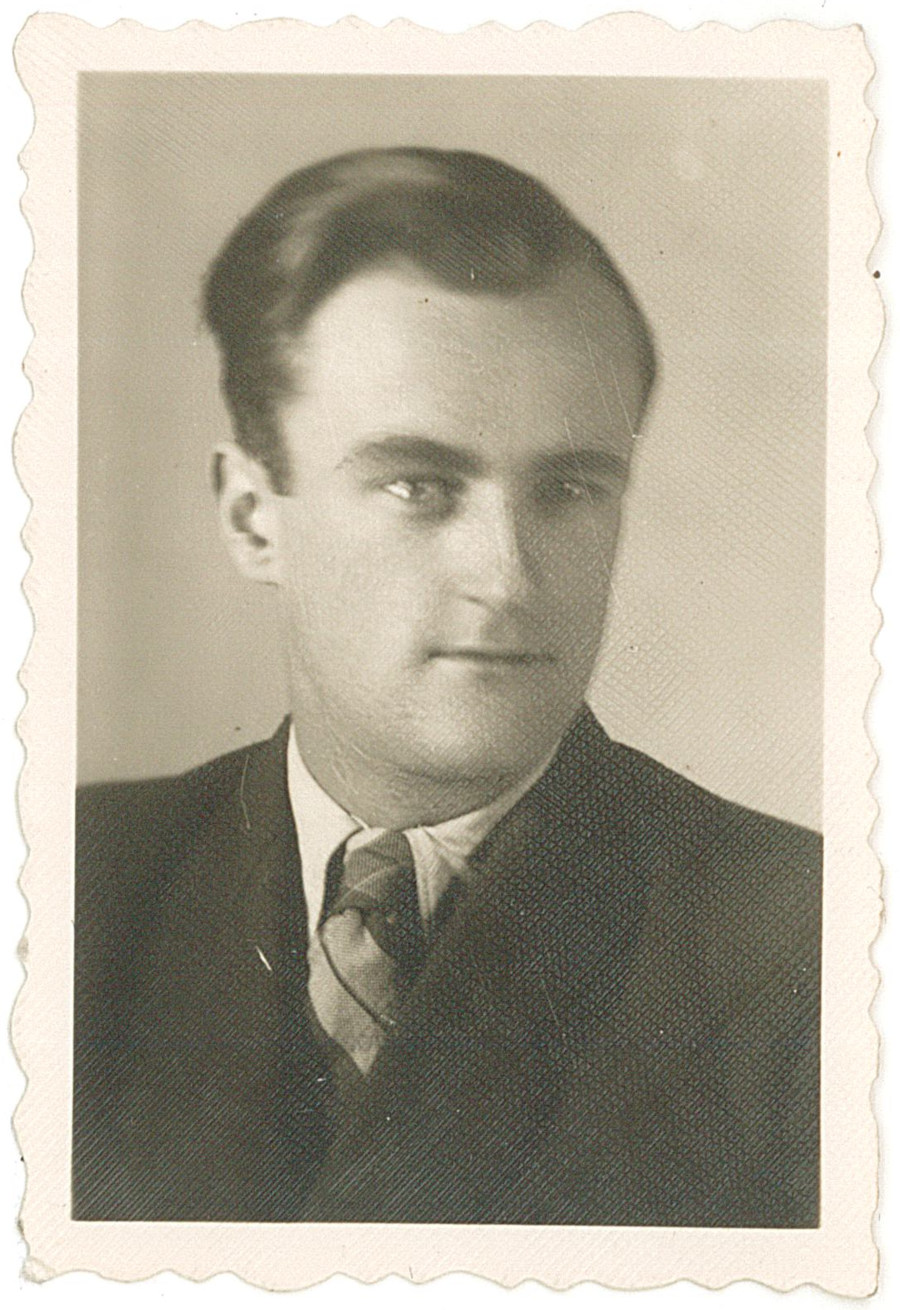

At the end of the war, as an officer of the Home Army, he was arrested by the Soviets. He managed to escape from prison and shortly thereafter emigrated with his father to the West. He ended up in the United States as a political refugee. In 1950, he was called up to the U.S. Army. Since he was not an American citizen, he refused military service. As a conscientious objector, his story went to the press and then to the court. After the case was discontinued, he left America and returned to Europe.

He graduated from the Sorbonne and became a historian and writer in exile. He died in 2010.