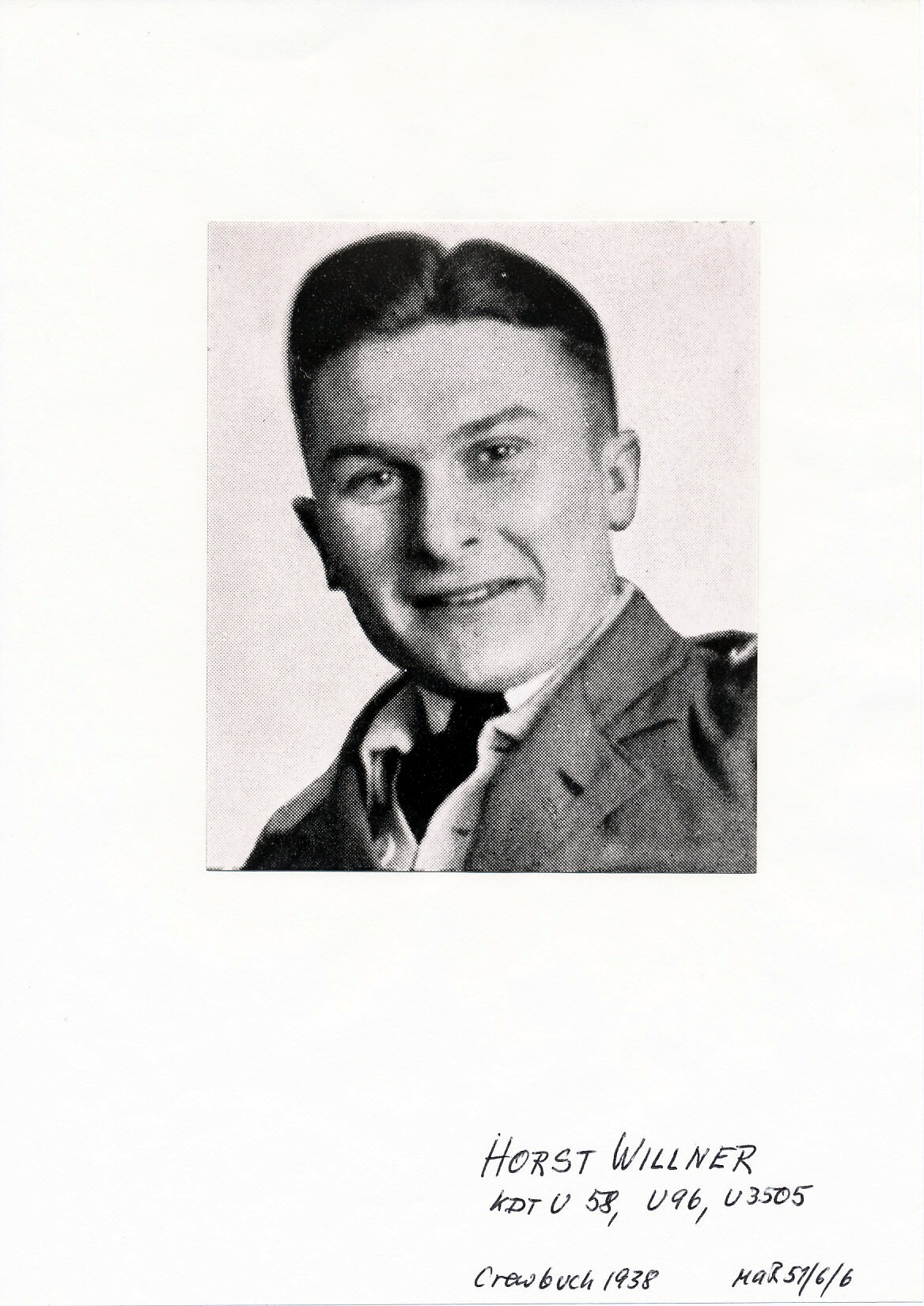

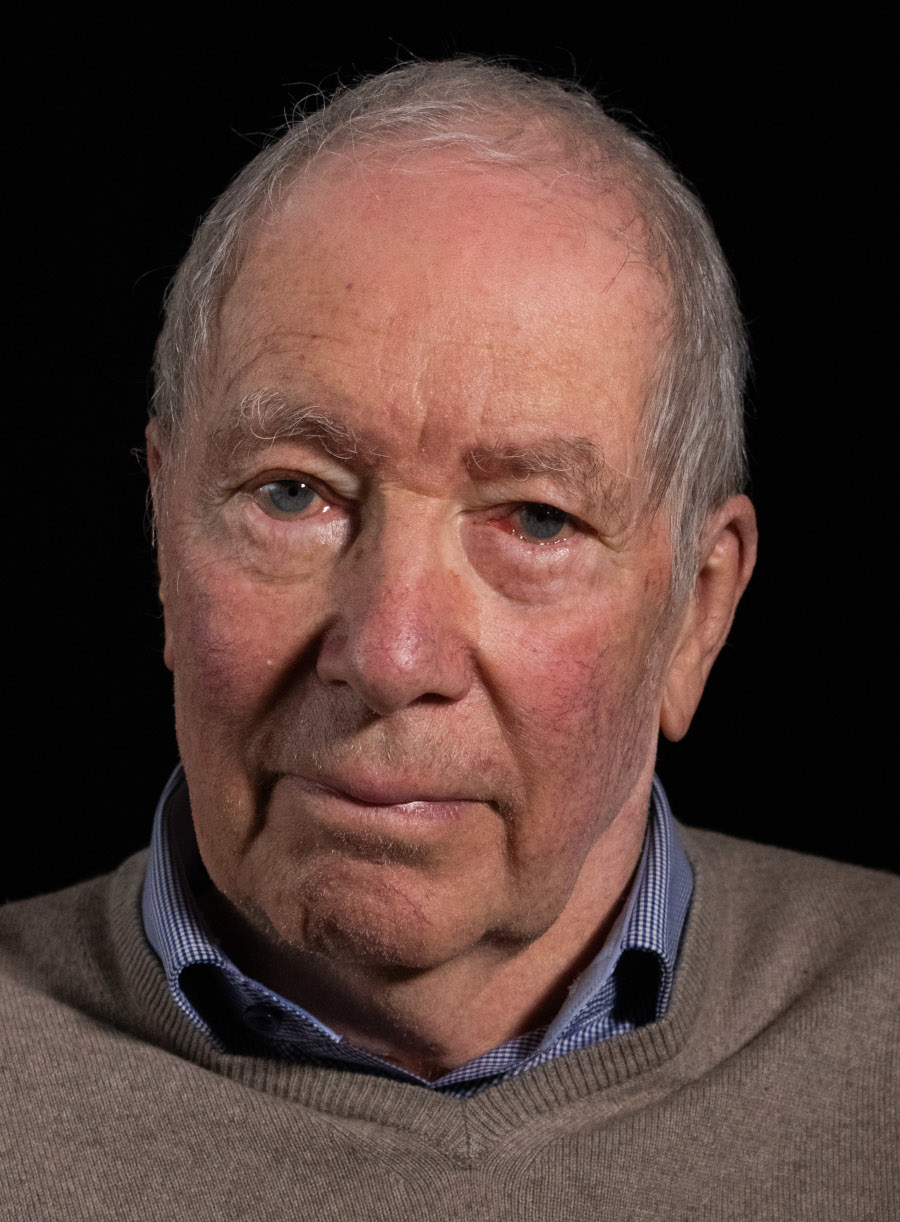

Horst Willner was a German U-boat commander. Between January and May 1945 he took part in a large naval evacuation operation bringing his family and a large number of civilians to safety with his U-boat.

Horst Willner was born in Dresden in 1919. He joined the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) in 1938 and commanded U-boats throughout the Second World War. In October 1944, he was given command of U-3505, a Type XXI submarine which was one of the most modern weapons of the German fleet.

In January 1945, the Red Army launched a large scale offensive aimed at East-Prussia. This resulted in a great wave of refugees among which were Willner’s wife, Ursula Menhardt, and their newborn daughter Barbara. Ursula and her daughter went to Gdansk where they boarded the Wilhelm Gustloff which was being used to evacuate the area. Just before the ship departed Willner picked up his family with the U-3505. By doing so, he saved his family’s life, as the Wilhelm Gustloff was attacked and sunk by a Soviet submarine, leaving only a few hundred survivors.

Willner’s decision to evacuate his family, as well as four female friends of his crew, was a clear violation of ordersas civilians were forbidden aboard German submarines. The stowaways thus had to be brought on board in secret. Ursula and the other women dressed up as sailors, while the baby was hidden in a pillow inside a duffel bag. U-3505 departed Gdansk in March 1945 and headed towards Hela. Here Willner picked up around 50 boys from the Hitler Youth, between the age of 12 and 16. All passengers and crew eventually safely reached Travemünde.

Willner was ordered to bring the U-3505 to Kiel to await further orders. Here the U-boat was destroyed in an American air raid in April 1945. Willner survived this attack. After the war was over he worked for a German shipping company. He died in 1999 in Bremen.